Why do we age whisk(e)y in a barrel?

Overeem Distillery’s Bond Store

With a great deal of care, patience, and a little bit of magic, whisky will spend a number of years in a barrel and come out at the end as the delicious, golden nectar that we all know and love. But why do we age whisky in a barrel? Also, what actually happens to that maturing whisky as the years go by?

If you ask a brewer, a distiller and a cooper ‘where does whisky get most of its flavour’ you might get a different answer from each. But there is no doubt that ageing a whisky in a barrel plays a great part when it comes to the final flavour profile of a whisky.

There’s a great deal of history behind why we started ageing whisky in barrels, but since then, science has evolved and so has our understanding of flavour and whisky production.

Using a cask for ‘flavour’ purposes is actually quite a modern technique. Casks do have a long history in the world of booze, but it was more so for storage and transportation purposes. Prior to the use of wooden casks, alcohol was kept and fermented in clay pots or bronze vessels

There are records dating back to at least 350 BC when Armenian wine was transported to Babylon in Mesopotamia using palm-oak casks. These cask-shaped containers had been developed to be watertight, stackable, and easy to transport, they were certainly a prototype to the casks we are used to seeing these days. It is believed that the art of constructing hooped barrels was kept secret by the Celts, who passed it down through generations as an honourable skill. For over 2000 years, casks were the go-to method for transporting a variety of goods, especially booze.

It is believed that the technique of ageing in casks for flavour was discovered by accident while transporting wines from one place to another.

Another theory suggests that sailors realised that their rum rations tasted better on their way back from a long sea voyage than when they left. Today, many liquids and even some foods spend time in casks, including Tabasco hot sauce, salted fish, wine, and spirits.

As we know now, countries have certain requirements and regulations when it comes to labelling something as ‘whisky’, the most common being the requirement to age the spirit in oak, or even just wood. Although spirits were being aged in casks for flavour purposes well before, it wasn’t until 1915 that Scotland introduced a legal act that brought about compulsory maturation.

The Immature Spirits Act 1915 brought about a compulsory two-year maturation period (increased to three years the following year) for Scotch whisky prior to sale.

At the time, Scotch whisky was viewed as one of the biggest threats to Scottish society by David Lloyd George. George blamed whisky for all the issues the country faced, and especially blamed young, immature whisky (or new make spirit) as being the biggest problem, as this unaged spirit allegedly had a more ‘severe impact’ on the drunkenness of the Scots. The Act was intended to slow down the consumption of whisky and increase the difficulty of being able to access the liquid.

Rather than diminishing the whisky industry, as was desired from this Act, it had the unintentional effect of improving the quality of Scotch whisky as the average age of whiskies rose. The outcome of this Act also filtered out a lot of poorer quality producers who were looking to churn out spirit in rapid turnaround times. This alternative result positioned Scotch whisky as a more premium product.

Now that ageing whisky in a cask had started to become law, a lot more attention was paid to the maturation process of whisky. If everyone now had to start maturing their whisky for ‘x’ amount of years, it’s worth ensuring that those years are well spent in a way that can greatly improve flavour.

In Scotland, whisky is required to be matured in oak specifically, but not all countries follow this rule. For other countries, the requirement is just ‘wood’.

Some countries such as Australia, Canada and Ireland, will have casks made from maple, acacia, cherry or chestnut wood. However, most distilleries will choose oak as their wood of choice when it comes to the maturation stage of whisky.

Oak is the perfect wood for casks due to its strength, suppleness and porosity. Oak is also quite soft compared to other woods, allowing it to be bent into shape a lot easier than other woods. The structure of oak ensures a very low chance of leakage while still allowing the whisky to breathe, which is vital to the maturation process.

Oak is quite a broad family of wood and can have many different species and variants. Different species of oak can contain differing proportions of extractive compounds, and they therefore contribute a distinctive individual flavour profile in the final whisky. The two most common oak species are:

1. American white oak (Quercus Alba) primarily grows in North America. It is very suited to whisky maturation as the trees are fast growing with tall straight trunks meaning it is high quality wood with a high level of vanillin. It typically offers flavour notes of coconut, vanilla, honey and nuts.

2. European oak (Quercus Robur) primarily grows in northern Spain. European Oak typically refers to Spanish Oak, but can also be known as English oak, Pedunculate oak, French oak or Russian oak. This oak is very porous. It offers flavour notes of spice and dried fruits.

Some other less common variants are Mizunara Oak, Swedish Oak, Hungarian Oak and German Oak.

Oak in general has the right grain structure to allow the spirit to move in and out of the wood with atmospheric pressure changes but without leaking. Spanish, Hungarian and French Oak (European Oak – Quercus Robur) – are often considered the more premium species to use due to their tighter grain and spicy, nutty, dried fruit character. Japanese Oak (Mizunara) is also highly respected and sought after. This species is well protected by Japan and is a lot more difficult to source, it usually comes with a premium price tag. American Oak (Quercus Alba) is a lot more accessible due to the sensible management of American Oak plantations as well as the fact that bourbon producers can only use an American Oak cask once.

The common American White Oak Tree (Quercus Alba) can be found in abundance across America.

Before any of these species of wood can be turned into a cask, there is a lot of preparation involved and a lot of processing. Once an oak tree has been felled, the logs are taken to a stave factory where the wood will be more carefully cut down into wooden planks, or staves. These staves are the individual pieces of wood that make up a cask. However, once the staves have been cut from the wood, you can’t go straight into making a cask.

To create a good quality cask, the rough staves must be left to season and dry out, this can take anywhere from a few months to a few years. During the drying process, which is also known as equilibration, the moisture content is reduced. If the staves are not properly dried, unequal shrinkage can occur, which can negatively affect the barrel when the liquid is already inside. To dry and season the wood used for casks, there are two main methods, ‘Air-Dried’ and ‘Kiln-Dried’.

(Pictured: A photo from the Independent Stave Company showing how they arrange their staves to dry out.)

The two methods are pretty self-explanatory, air-drying is leaving the oak outside, exposed to the elements to dry slowly over time. Kiln-drying is directly heating the oak to dry it in a more controlled manner. Both have their uses, both displaying different results. An experiment was conducted by the Whiskey Tribe observing the effects of air-drying vs kiln-drying on many different variables that contribute to the finished whisky (pictured).

A great way to experience these differences yourself is through the Benromach ‘Contrasts’ series, where they have released two expressions of basically the same whisky, but with one being matured in air-dried wood and one being matured in kiln-dried wood.

Once the oak has been dried to its desired levels, those staves can then be sent to the cooperage where a cooper will masterfully assemble a cask, having it ready to be filled with new-make spirit.

The quality of the wood used for making the cask certainly plays a part in determining its success and its ability to last decades. But it’s the skill of the cooper that plays the final role when it comes to the success of a cask.

A cooper is the tradesperson responsible for hand crafting the casks that whisky goes into. Traditionally, many Scottish distilleries used to have their cooperage on-site, but today, only a few directly employ coopers. At the turn of the millennium, only 250 skilled coopers were in Scotland. However, thanks to active apprenticeships, that number has since risen to 300 in recent years.

Crafting watertight barrels is a highly skilled and intricate process. Some liken it to solving a puzzle. For instance, a hogshead barrel, which holds approximately 230-250 litres of liquid, typically consists of 31-33 staves that are roughly 98cm/39" long and 3cm/1.25" deep, with varying widths. They need to be figured out and assembled perfectly so that they are structurally sound and that no liquid can leak from the cask. When receiving a second-hand cask, they don’t always arrive assembled, sometimes they are shipped as individual staves that need to be put back together. Hogsheads are a Scottish tradition created by combining the staves of five ex-bourbon casks that can hold roughly 200 litres each with new heads to create larger casks. The staves are held together by six steel hoops and 12 rivets.

“…sometimes when we purchase barrels via a broker, to save on shipping they get flat packed on a pallet. This saves on space but can lead to some hairy “Ikea Nightmare” moments if they aren’t numbered correctly.” -Charlie Johnson, Timboon Distillery

Outside of Hogsheads and Barrels (ASB), there are many different sizes and volumes of casks used for whisky maturation. Unfortunately not all terminology and sizes are universal, you can sometimes find different answers depending on who you ask (some refer to a quarter cask as 50L where some will refer to a quarter cask as 125L). For the sake of this blog, these are the sizes and terminologies I use but take with a grain of salt.

Blood-tubs- 30L to 40L

Octaves- 50L

Quarter Casks-125L

Barrel (American Standard Barrel)- 200L

Hogshead- 230-250L

Port-Pipes- 350L+

Butt- 500L

Puncheon- 700L

(Pictured: An assortment of different casks at Belgrove Distillery)

The smaller the barrel, the greater the contact between the spirit and the wood, which results in different maturation characteristics coming on in shorter amount of time. For instance, in an Octave, whisky interacts with the cask much faster than in a Butt due to more of the wood’s surface area being in contact with the liquid. Different sized casks will always give different results when it comes to maturing a whisky. Usually the size of a cask is deliberately picked depending on what the distillery is trying to achieve from their whisky and the climate they are in.

“We use mostly 100L to 220L casks. Basically I ask the cooper to waste as little wood as possible and our racking system allows for any size barrel up to 220L. I find the 20L and 50L casks are ready quickly but still have some volatility, whereas we prefer the larger casks. ‘Speeding up’ the process is not our goal – making good whisky is the plan!”-Karin Spencer, Bogan Road Distillery.

“At Timboon we use a variety of Cask sizes. 50lt, 100lt, 220lt, 330lt, and (recently filled) 500lt barrels. We use different sized casks of the same wood (and fill) type to blend a whisky with the best attributes. Nose, Mouthfeel, flavour etc.”-Charlie Johnson, Timboon Distillery.

Regardless of size, most casks are heat-treated in some way; they can be either charred, toasted or both. These heat treatments are essential to get the flavour congeners out of the wood.

Charring is a heat treatment where the wood of the cask is ignited. It helps to break down the structure of the oak, allowing for an easier and deeper penetration by the spirit and a more intense interaction with the flavours produced through lignin degradation. Lignin degradation is when the inside of casks are either toasted or charred, thus breaking the lignin (structure of the wood) down into other compounds. Examples of these compounds are acids, sugars, aldehydes, vanillin.

There are generally four grades of charring: No.1 = 15 seconds No.2 = 30 seconds No.3 = 35 seconds No.4 = 55 seconds. No.4 heavy char creates layers of charcoal on the inner surface of the staves, giving it a coarse, bumpy surface that is comparative to alligator skin, hence its nickname, the ‘alligator char’. In Australia, Morris Whisky speaks of a level of char that goes further than alligator char. They like to call this level ‘crocodile char’ as we don’t have alligators in Australia, only crocodiles. This level of char is so extreme that the cask can only be used once. After use, the cask must be discarded. This particular process can impart such a heavy smoky, burnt wood and intense char aroma to a completely unpeated whisky. This cask is used to mature their Smoked Sherry and Smoked Muscat releases.

Toasting is a heat treatment where the inside of the cask is heated for about 15 minutes at 350°C (662°F). This browns the wood and allows heat to penetrate in, thus creating what is known as the red layer. This is a layer where lignin degradation has occurred and is about three millimetres thick, between the char and the untouched wood. Toasting is generally classed as light, medium or heavy.

(Pictured: Casks being toasted over an open fire and casks being charred with direct flame on the wood)

In the bourbon industry, it is a requirement that the spirit has to me aged in a charred, virgin American Oak cask, so you will find that every ex-bourbon cask has been charred. Other distilleries that aren’t making bourbon are also now using what are termed as virgin oak casks. Virgin Oak refers to a cask which has not had any previous contents in it before it is filled with new make spirit. Virgin oak casks impart a great deal of colour and flavour in a relatively short amount of time compared to other casks.

A lot of sherry casks and other fortified wine casks are usually made from a variety of European Oak. When using European Oak for sherry casks, the sherry wood is not charred, only toasted, usually over the flames of a little oak fire for about an hour. If ageing a whisky in ex-sherry casks, the sherry wood tends to give more of that dried fruit, Christmas pudding and sherry flavour. Whereas when ageing in ex-bourbon casks, the bourbon wood is a much drier wood flavour. It often tends to give a pencil shaving type of note as well as all of the more familiar vanilla, buttery tones, coconut and tropical fruits.

If an ex-bourbon cask is used for new make spirit, this is classed as a 'first fill'. If it is subsequently used again for another batch of new make spirit, it is classed as a 'second fill'. Once a cask has been used for three or even four fills, the cask has a lot less to offer. The wood becomes progressively exhausted and will impart little colour, texture and flavour. This is due to the wood’s ‘additive’ compounds having been removed from the active wood layer by previous successive fillings.

Using a cask is very much like using a tea bag, the more you use it the less flavour and colour it has to offer. This is where cask rejuvenation comes in, also known as shaved, toasted, re-charred (STR). A cask is considered rejuvenated when it is de-charred and re-charred. De-charring is when a few millimetres of wood are shaved from the inside of the cask, revealing a new layer that can be re-charred with a ‘red layer’ produced in the wood under the char. This red layer is where the lignin thermal degradation has occurred. However this can only be done so many times, as the staves of the cask are being thinned each time, reducing the structural integrity of the cask.

“We sometimes do an STR after emptying the whisky and send the re-coopered barrel to a brewery for barrel aged stouts. We’ve even started filling some older casks with molasses spirit to make rum. Getting a useful 3rd fill from a cask.”- Charlie Johnson, Timboon Distillery.

(Pictured: A bottle of Timboon’s rum, brought to life by reusing 2nd fill casks for maturation)

The best way to understand the basics of whisky maturation and the interaction between the liquid and the cask is something I like to call the ‘Tea Bag Analogy’. It is best described as this; Think of your cask as a tea bag and think of the new make spirit as the water. More specifically, think of the ABV% of your spirit as the temperature of the water you are using to brew the tea. When you are brewing your tea, you pull out a fresh, unused tea bag and pop it in your mug. You have the kettle boiled, and you pour the water in and after a few seconds of the tea bag steeping in the water, you get a little bit of colour. If you pull the tea bag out after a few seconds, it probably won’t be the best cuppa you’ve ever had. You probably won’t really be able to taste much of the tea, so you must let it sit, give it some time, really let the water extract the flavour from the tea.

Now on the other hand, you don’t really want to leave it to steep for too long either. The longer you leave the tea bag in there and that water stays hot, you will continue to extract from the tea, sometimes bringing out some more of those bitter, tannin flavours that you might not be after. If you parallel this procedure with whisky maturation, you start off with your new, virgin oak cask. You have your new make spirit ready at entry proof (probably around the low 60% ABV mark) and fill the cask with it. In a short amount of time, you will start to get colour to the whisky, but if you took it out then, it probably won’t be the best tasting whisky you’ve had. You have to let it sit, give it some time, really let the whisky interact with the oak and develop. Now, on the other hand, you don’t really want to leave it to mature for too long either, as you might start to extract some unpleasant flavours, ‘over-oaking’ the whisky and starting to dull some of those complexities and nuances that took so long to develop.

If you take that same tea bag that you’ve just used and tried to use it again for another brew, this is effectively using an ex-bourbon cask. You’re not going to get all those original flavours you got from the first use, and you might need to let it sit for a bit longer to extract the desired flavours you are after. That tea bag can only be used so many times before it eventually has nothing to give.

On the parallel side of this analogy, the temperature of the water is similar to the ABV% of the new make spirit. If you try and brew the tea with room temperature water, it’s going to be quite a slow process, and it might not extract enough of the desired flavours you are after. If the ABV% of the spirit going into a cask is too low, it’s a similar deal. The other end of the spectrum is also true, you often don’t need to be brewing a tea with 100°C boiling water, usually 85°C-90°C is ideal. As with the spirit, if it is too high of an ABV% it can extract undesirable characteristics during the maturation process. For a lot of distilleries, the sweet spot usually sits between 60%-70% ABV.

Nerdy Stuff:

Now it’s time for the real nerdy stuff, to truly answer not only the question of why we age whisky in a cask, but what actually happens when you age whisky in a cask.

When new-make spirit goes into a cask, some changes start to happen straight away. But most of the big, important changes that we look for happen over a longer period of time. As the whisky matures, the cask basically ‘breathes’ and the liquid moves in and out of the wood. Oak, being quite a porous wood, allows the liquid to penetrate the staves of the wood, then leave the wood, taking on flavour, texture, aroma and colour from the oak. However, we aren’t able to retain all that liquid, as the cask ‘breathes’, we lose some liquid to Angels’ Share.

During maturation, a proportion of spirit is lost through evaporation. Ethanol, water and some other congeners turn into gases inside the cask and gaseous exchange can be lost to the atmosphere. In Scotland, approximately 1- 2% of the cask volume will be lost each year to what is called the Angels’ Share. The Angels' Share refers to the amount of ethanol and water that is lost due to evaporation during ageing.

“In Tasmania we have a variable but generally colder climate. Our casks don’t do a great deal in the cold weather and then speed up their changes during the summer. Some lose alcohol, some lose more volume than others – this is probably largely influenced by where they are stored in the bond store – e.g. near a warm western tin shed wall as opposed to a southern wall, but also influenced by the wood grain and even the spirit that is in the cask. Starting as an independent bottler has given me some interesting outcomes and insight from putting different spirit in the same wood. We put the spirit in the cask at 63.4% and some go up – one as high as 65.5% and others down – one was 62% natural cask strength. (Angels’ Share) is climate and wood grain dependent. In our little corner of Tasmania we lose about 3% per year to the Angels. Some warmer parts of the world the percentage is much higher.”-Karin Spencer, Bogan Road Distillery

Depending on where you are in the world, over a 10 year period, a cask could have lost anything from 10-30% (or sometimes more) of its liquid to the Angels' Share. Climatic conditions have a considerable effect on maturation. The climatic conditions relevant to maturation are temperature and humidity. Temperature affects the rate at which both ethanol and water is lost during maturation. Higher temperatures=more volume lost. Humidity affects the relative rate at which ethanol is lost compared to water. Higher humidity=more ethanol loss=ABV% goes down. Lower humidity=more water loss=ABV% goes up.

Take the typical conditions of Scotland, for example. The climate is cool and wet. That means ethanol evaporates relatively more quickly than water, thus leading to a reduction in ABV in the cask over time. In India, for example, climatic conditions are much hotter and drier, meaning more water is lost relative to ethanol. Therefore, during maturation in India, the ABV in the cask will increase over time.

Different casks obviously influence the final flavour in different ways as does the entry proof. Certain compounds are extracted more efficiently by the water phase while others in the ethanol phase. The filling strength or entry proof (ABV% of new-make spirit when entering the cask) is vital. Some compounds such as lactones are more soluble in higher alcohol concentration, so would have more influence on flavour if the filling strength was higher. The opposite is true for compounds that are more soluble in a lower alcohol concentration.

During maturation, you will find that a lot of the changes that happen to the whisky can fall under 3 categories: subtraction, addition and transformation.

Subtraction-The charcoal layer of a cask also acts as a filtration system, helping to remove unwanted chemical compounds and flavours, such as sulfur, from the new spirit. These compounds may have formed during the distillation process, particularly where worm tub condensers have been used or the distillation has been run too fast.

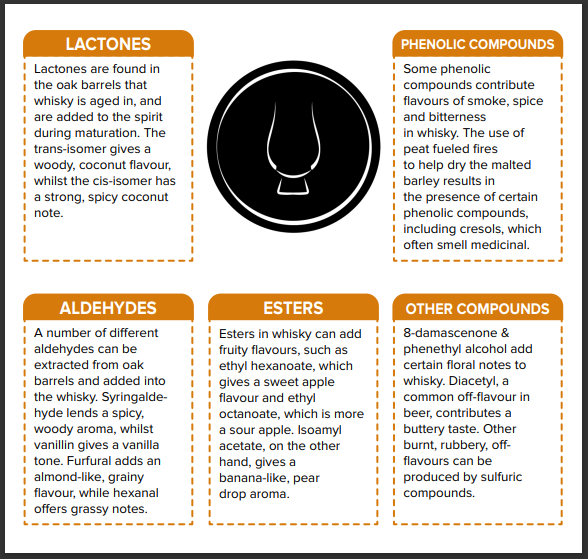

Addition- While in the cask, a number of reactions are going on to alter the aroma and flavour profile of the liquid. These ‘addition’ reactions occur when the cask directly adds certain chemical compounds and flavours to the whisky. The whisky extracts the available oak degradation compounds formed during cask manufacture.

These compounds derive from the natural oak polymers found in the wood. Cellulose, hemicelluloses, lignin, oak tannins and the char layer. Different oak derived compounds are imparted at different stages during the maturation process. This means that, for certain whiskies, the most significant flavour uptake is immediately following filling, while others take longer to develop through oxidation as part of the ‘transformation’ changes.

The more common compounds added to the whisky from a cask are vanillin, lactones and tannins.

Transformation- Cask driven oxidation results in various flavour adjustment by means of naturally occurring reactions during maturation. During these reactions, alcohols, organic acids and aldehydes experience varying degrees of transformation to form alternative compounds. Certain compounds that originate in the initial spirit undergo complete changes after reacting with the oak to transform into a different set of flavours and aromas.

During fermentation, some of the congeners that form are known as esters. These esters are responsible for a vast array of flavours and aromas. After being created during the fermentation process, they can carry over into the spirit after distillation and into the final product after maturation. The various esters and organic acids present in the raw new make spirit also take part in these naturally occurring transformation reactions during maturation. This process is known as esterification and creates new and different esters when certain compounds in the spirit react with the cask. This means the original levels present in the new make spirit change during maturation.

(An example of some of the esters you can find in whisky)

Another family of chemical compounds known as phenols can undergo ‘subtraction’ changes during maturation. When talking about phenols in whisky, they are usually in the same conversation as peat smoke, and PPM of a peated whisky, but phenols are not just responsible for big smoky flavours. Sometimes, you can find phenols present in unpeated whisky. The presence of phenols does not always mean there will be a presence of smoke, there are many subcategories of phenolic compounds. The most common and most abundant introduction of phenols to your whisky is usually through ‘peating’ your whisky, this occurs during the kilning process. It’s at this point that phenols from the burning peat will cling to the barley, these phenols will continue to be present throughout fermentation, distillation and maturation (to a degree). A more specific subcategory of phenols that exist when you smoke things are called cresols. The most common example of cresols in everyday life can be found in disinfectants, and more specifically, meta-cresol is found to have antiseptic and antibiotic properties. Due to this, they are used in the production of band-aids (keep this in mind next time you have a peated whisky that smells ‘medicinal’).

When it comes to ageing whisky in a barrel, these phenolic compounds are actually some of the compounds that tend to start disappearing earlier on. Hence why they fall under the ‘subtraction’ category.

There are a few phenolic compounds that are quite common in whisky:

Eugenol- part of the ‘addition’ category, a phenolic compound that is usually introduced by the cask, eugenol brings a lot of ‘spice’ characteristics to the whisky. Eugenol is most commonly recognisable in clove oil.

Syringol- responsible for smoke aroma, usually introduced via burning peat. Can also come from the cask char.

Guaiacol- Responsible for smoke flavour, usually introduced via burning peat. Can also come from the cask char.

Throughout maturation, a lot of these phenolic compounds can disappear over time, which is why if you want a really big smoke bomb of a whisky, its better to opt for something a bit younger. There are some cases of a peated whisky being aged for such a period of time, that a lot of that smoke has practically disappeared. Laphroaig 25 year old seems to be an example of this for some people.

When new make spirit goes into a cask to age, sometimes there is a definitive plan for the journey of that liquid, or sometimes its path becomes clearer later on.

Depending on the distillery, the business model and the core range of the brand, an ageing cask of whisky could be destined for many different paths. It might reveal itself to be an excellent candidate for a Single Cask selection down the line. It might be one of many ex-bourbon cask aged whiskies to be married together for a core range release. Or sometimes it might start off with one plan, but over time ends up needing to be ‘finished’ in an alternative cask to give it the character it needs.

(Pictured: The Glenmorangie 10, an expression made up entirely of ex-bourbon cask aged whisky.)

Whisky can be matured entirely in ex-bourbon or sherry oak casks for its whole life, but sometimes, a secondary maturation in a different cask is applied to the whisky. This is called a cask finish. Whiskies can be finished in a variety of casks, including rum, ex-Islay (for a smoky finish), Sauternes, Madeira, port (tawny), red and white wine, Muscat, and even beer or cider. Each finish imparts a unique flavour and character to the whisky.

Ageing whisky in a barrel is more than just a legal regulation, it truly allows us to sit in the drivers seat of flavour and steer the whisky in the direction we want it to go. It’s a more detailed and intricate process than just ‘fill a barrel, stash it away and leave it for 10 years’. The art, the craft and the magic of whisky maturation is something that should never be overlooked.